What the Machines Still Don’t Know

My imagination was restless.

Always questioning. Always building.

Sometimes with my hands—often makeshift contraptions, duct-tape inventions, and slingshots that occasionally shattered car windows. (Sorry, Mom.)

But more often, it was invisible work.

Quiet ideation.

Out of nothing but wonder, I’d dream up gadgets and tools I couldn't explain yet. Interfaces that answered your questions, machines that knew things.

"What if you could ask a screen anything, and it would know what you meant? Like talking to a librarian with access to all the world's knowledge?"

One of my earliest science teachers said something I never forgot: "Technology is about improving life for humankind."

That line stuck to my skull.

It rewired how I thought.

I wasn't trying to build products.

I was trying to solve puzzles no one had.

I wanted the world to feel more aligned with the beauty I could imagine.

Not with code. With curiosity.

And that curiosity had a home, for a while, in an unlikely place: the Crystal Mall.

I was trying to make sense of the world,

one aesthetic heartbreak at a time.

And so I built it in my head—inside the Crystal Mall.

A fluorescent-lit temple of the early 2000s.

Echoing tile floors. Skylights casting ghost-light across the food court.

The scent of Auntie Anne's pretzels mixing with Panda Express and teenage angst.

I wandered past JCPenney mannequins and through the forbidden glow of Spencer's Gifts, where lava lamps and weird gifts whispered dark secrets to anyone brave enough to linger.

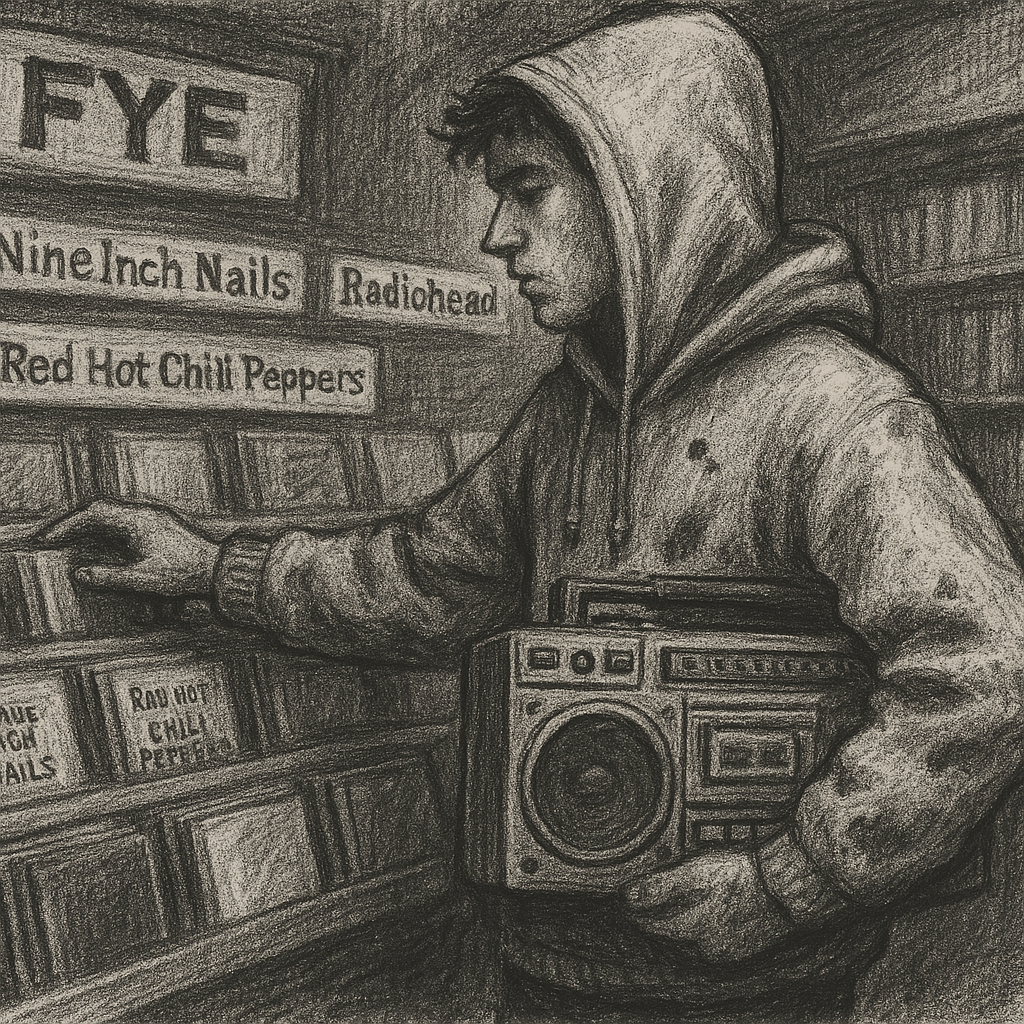

I didn't just buy CDs at FYE; I curated them.

Jewel cases lined up like artifacts.

My mom taught me how to hunt— Nine Inch Nails, Radiohead, and Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Armed with my boombox and pretzel-stained hoodie.

This was dead mall core at its finest: half sacred, half crumbling.

Architecture built to move product, not people.

A world made of rectangles and resale.

I still filled it with imagination.

But I also knew there was more.

My grandparents took me to places with weight—Europe, the Southwest.

Cathedrals and sandstone. Intentional spaces.

Places where architecture and nature meant something.

Scenes that told stories.

Walls that held memory.

That contrast between the imagined and the assembled, the mass-produced and the meaningful—stuck with me.

I didn’t want to live in someone else's box.

I wanted to invent the next one.

Somewhere along the way, the dynamic changed.

Dreaming is different when the tools start dreaming with you.

When the gap between what's in your head and what you can build gets smaller—and then flips—when the thing you imagined starts building you back.

The tools caught up.

The ideas I used to sketch in my head—those half-imagined systems and interfaces—they weren't theoretical anymore. They were real. And one day, I watched them outrun me.

It happened the first time I asked an AI to help me design an app.

I gave it a rough concept—something I'd been mulling over for weeks. In seconds, it responded with logic flows, layouts, feature sets. Dozens of variations.

Some were expected.

Other things I hadn't even thought of yet.

The machine wasn't just following my idea.

It was expanding it.

Take my task manager, for example.

I've always dreamed of a clean slate every morning, but with unfinished tasks carrying over intelligently. Not as guilt, but as fresh context for the things that truly matter.

I explained that.

The AI ate it and spit out a flood of responses: versions, iterations, even moods. It filled in gaps I hadn’t seen. It surfaced possibilities I didn't know I wanted.

That's when it hit me:

The challenge isn't getting machines to create anymore.

It's knowing which creations matter.

And that's the paradox of 2025:

Machines can build almost anything.

But they still don't know why.

They don't understand context.

At least not in the human sense—the kind shaped by memory, emotion, or lived experience.

They don't know what it feels like to be late on rent, to lose someone slowly, to walk through a grocery store and suddenly remember a childhood smell.

They don't know which problems haunt us and which ones are just a passing itch.

That's still our job.

To decide what's worth building.

To ask better questions.

To protect the signal from the noise.

To care.

So now, I'm back in a familiar role.

Not as a coder. Not even as a maker.

But as a curator again—

a pattern-spotter, a taste-haver, a translator between potential and purpose.

Because it turns out, that kid with the boombox and the pretzel hoodie wasn't just dreaming up cool gadgets.

He was dreaming up meaningful tools for real people.

He didn't have the language yet.

Now I do.

And in a world where anything is possible, that's what actually matters.